Adapted from Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future

Attempting to make sense of intelligence’s multiple aspects played a key early role in my thinking. At that time, the fact that intelligence has multiple aspects was only beginning to be appreciated. I recognized that creative processes drew on a variety of different ways of knowing, and did so in different ways at different points along the way. I also recognized that I would need to give some special attention intelligence’s more kinesthetic/body aspects and more imagination/symbol-making aspects. At our time in culture, these more creatively germinal aspects of intelligence tended to be particulary foreign to people. If people are conscious of such sensibilities at all, they tend not to think of them as intelligence.

Important insights came to me during this time of initial reflections on intelligence and its workings. Early on, my primary interest lay specifically with creative process. But as I was introduced in my training to developmental psychology—and in particular, more systemic developmental thinkers such as Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg—it became clear to me that a similar intelligence-related progression worked beneath the surface with our personal formative stories. The surprising recognition that we see a similar cognitive progression with culture’s story came soon thereafter—and with it, Creative Systems Theory was born.

Creative Systems Theory emphasizes that human intelligence is more multifaceted than before we’ve been capable of appreciating. And it goes on to describe how intelligence’s multiplicity is structured specifically to support and drive formative process, a notion that should not take us by surprise if our toolmaking natures is what most defines us.

Multiple Intelligences

The basic notion that intelligence is multiple is itself important. Culturally mature understanding and actions require that we bring to bear more aspects of intelligence—more of our diverse ways of knowing—than we’ve traditionally made use of at one time. Cultural Maturity’s cognitive changes invite us to step back and engage intelligence as a whole with a newly systemic completeness.

Mature systemic perspective requires that we apply our intelligence in the rational sense—indeed that we do so with new precision. But it also necessarily engages other aspects of intelligence. Culturally mature understanding consciously bridges facts with feelings, the workings of the imagination with more practical considerations, observations of the mind with things only our bodies can know. It requires that we consciously draw on the whole of ourselves as cognitive systems.

We encounter something related with personal maturity. We associate the best of thinking in our later years not just with knowledge, but with wisdom. Knowledge can be articulated quite well by the intellect alone. Wisdom, however, requires a more fully embodied kind of intelligence, one that draws on all of who we are. Wisdom results not just because we better include all the aspects of our questions, but also because, when seeking answers, we don’t leave out essential parts of ourselves. We draw on all of ourselves as cognitive systems.

If the concept of Cultural Maturity is correct, we should expect an analogous result at a species level, and it is essential that we do. The future will require something beyond just being smarter in the decisions we make. Given the magnitude of the choices we confront and the potential consequences if we chose poorly, it is essential that our decisions be not just intelligent, but wise.

The importance of more deeply engaging the whole of intelligence is reflected in the best of contemporary understanding. We hear physicist Niels Bohr assert that, “When it comes to atoms, language can be used only as poetry.” We are better appreciating how mind and body, far from being separate worlds, interlink through a complex array of communications molecules. Likewise, educational circles vigorously debate whether IQ adequately measures the whole of intelligence. (In the most recent popular round in this conversation, Daniel Goleman contends that we need also to measure EQ—emotional intelligence.)

Intelligence and Creative Systems

We could use a variety of multiple intelligence frameworks to bring detail to our thinking about cognition’s multiplicity, but Creative Systems Theory’s formulations have particular significance. Creative Systems theory points out that our toolmaking nature means that human intelligence must at least powerfully support formative process. It goes on to describe how human intelligence is specifically structured to drive and facilitate creative change.

Creative Systems Theory proposes that we are the uniquely creative creatures we are not just because we are conscious, but because of the particular ways the various aspects of our intelligence work, and the ways in which they interrelate.

It describes how our various intelligences—or we might say sensibilities to better reflect all they encompass—relate in specifically creative ways. And it goes on to delineate how different ways of knowing, and different relationships between ways of knowing, predominate at specific times in any human change processes. It ties the underlying structures of intelligence to patterns we see in how human systems change—thereby both helping us better understand chance and hinting at the possibility that we might better predict change.

Creative Systems Theory identifies four basic types of intelligence. For ease of conversation, I will refer to them here as the intelligences of the body, the imagination, the emotions, and the intellect. (CST used fancier language.)Creative Systems Theory proposes that these different ways of knowing represent not just diverse approaches to processing information, but that they are the windows through which we make sense of our worlds—and more than this, that they describe the formative tendencies that lead us to shape our worlds in the ways that we do.

It also argues that our various intelligences, in the end, work together in ways that are not just collaborative, but specifically creative.Human intelligence is uniquely configured to support creative change. Our various modes of intelligence, juxtaposed like colors on a color wheel, function together as creativity’s mechanism. That wheel, like the wheel of a car or a Ferris wheel, is continually turning, continually in motion. The way the various facets of intelligence juxtapose makes change, and specifically purposeful change, inherent to our natures.

The following diagram depicts these links between the workings of intelligence and the stages of formative process:

Formative Process and Intelligence

A brief look at a single creative process—let’s take as our example the writing of a book such as this one—helps clarify things. In subtly overlapping and multi-layered ways, the process by which this book came to be took me through a progression of creative stages and associated sensibilities. Creative processes unfold in varied ways, but the following outline is generally representative:

—Before beginning to write, my sense of the book was murky at best. Creative processes begin in darkness. I was aware that I had ideas I wanted to communicate. But I had only the most beginning sense of just what ideas I wanted to include or how I wanted to address them. This is creativity’s “incubation” stage. The dominant intelligence here is the kinesthetic, body intelligence, if you will. It is like I am pregnant, but don’t yet know with quite what. What I do know takes the form of “inklings” and faint “glimmerings,” inner sensings. If I want to feed this part of the creative process, I do things that help me to be reflective and to connect in my body. I take a long walk in the woods, draw a warm bath, build a fire in the fireplace.

—Generativity’s second stage propels the new thing created out of darkness into first light. I begin to have “ah-has”—my mind floods with notions about what I might express in the book and possible approaches for expression. Some of these first insights take the form of thoughts. Others manifest more as images or metaphors. In this “inspiration” stage, the dominant intelligence is the imaginal—that which most defines art, myth, and the let’s-pretend world of young children. The products of this period in the creative process may appear suddenly—Archimedes’s “eureka”—or they may come more subtly and gradually. It is this stage, and this part of our larger sensibility, that we tend to most traditionally associate with things creative.

—The next stage leaves behind the realm of first possibilities and takes us into the world of manifest form. With the book, I try out specific structural approaches. And I get down to the hard work of writing, and revising—and writing and revising some more. This is creation’s “perspiration” stage. The dominant intelligence is different still, more emotional and visceral—the intelligence of heart and guts. It is here that we confront the hard work of finding the right approach and the most satisfying means of expression. We also confront limits to our skills and are challenged to push beyond them. The perspiration stage tends to bring a new moral commitment and emotional edginess. We must compassionately but unswervingly confront what we have created if it is to stand the test of time.

—Generativity’s fourth stage is more concerned with detail and refinement. While the book’s basic form is established, much yet remains to do. Both the book’s ideas and how they are expressed need a more fine-toothed examination. Rational intelligence orders this “finishing and polishing” stage. This period is more conscious and more concerned with aesthetic precision than the periods previous. It is also more concerned with audience and outcome. It brings final focus to the creative work, offers the clarity of thought and nuances of style needed for effective communication.

—Creative expression is often placed in the world at this point. But a further stage—or more accurately, an additional series of stages—remains. It is as important as any of the others—and of particular significance with mature creative process. It varies greatly in length and intensity. Creative Systems Theory calls this further generative sequence Creative Integration. With the process of refinement complete, we can now step back from the work and appreciate it with new perspective. We become better able to recognize the relationship of one part to another. And we become more able to appreciate the relationship of the work to its creative contexts, to ourselves and to the time and place in which it was created. We might call creativity’s integrative stages the seasoning or ripening stages. Creative Integration forms a complement to the more differentiation-defined tasks of earlier stages—a second half to the creative process. Creative Integration is about learning to use our diverse ways of knowing more consciously together. It is about applying our intelligences in various combinations and balances as time and situation warrant, and about a growing ability not just to engage the work as a whole, but to draw on ourselves as a whole in relationship to it. As wholeness is where we started—before the disruptive birth of new creation—in a certain sense Creative Integration returns us to where we began. But because change that matters changes everything, this is a point of beginning that is new—it has not existed before.

Creative Systems Theory applies this relationship between intelligence and formative process to human understanding as a whole. It proposes that the same general progression of sensibilities we see with a creative project orders the creative growth of all human systems. It argues that we see similar patterns at all levels—from the growth of an individual, to the development of an organization, to culture and its evolution. A few snapshots:

—The same bodily intelligence that orders creative “incubation” plays a particularly prominent role in the infant’s rhythmic world of movement, touch, and taste. The realities of early tribal cultures also draw deeply on body sensibilities. Truth in tribal societies is synonymous with the rhythms of nature and, through dance, song, story, and drumbeat, with the body of the tribe.

—The same imaginal intelligence that we saw ordering creative “inspiration” takes prominence in the play-centered world of the young child. We also hear its voice with particular strength in early civilizations—such as in ancient Greece or Egypt, with the Incas and Aztecs in the Americas, or in the classical East—with their mythic pantheons and great symbolic tales.

—The same emotional and moral intelligence that orders creative “perspiration” tends to occupy center stage in adolescence with its deepening passions and pivotal struggles for identity. It can be felt with particular strength also in the beliefs and values of the European Middle Ages, times marked by feudal struggle and ardent moral conviction (and, today, in places where struggle and conflict seem to beforever recurring).

—The same rational intelligence that comes forward for the “finishing and polishing” tasks of creativity takes new prominence in young adulthood, as we strive to create our unique place in the world of adult expectations. This more refined and refining aspect of intelligence stepped to the fore culturally with the Renaissance and the Age of Reason and, in the West, has held sway into modern times.

—Finally, and of particular pertinence to the concept of Cultural Maturity, the same more consciously integrative intelligence that we see in the “seasoning” stage of a creative act orders the unique developmental capacities—the wisdom—of a lifetime’s second half. We can also see this same more integrative relationship with intelligence just beneath the surface in our current cultural stage in the West in the advances that have transformed understanding through the last century.

We associate the Age of Reason with Descartes’s assertion that “I think, therefore I am.” We could make a parallel assertion for each of these other cultural stages: “I am embodied, therefore I am”; “I imagine, therefore I am”; “I am a moral being, therefore I am”; and, if the concept of Cultural Maturity is accurate, “I understand maturely and systemically—with the whole of myself—therefore I am.” Cultural Maturity proposes that the discussion you have just read about intelligence’s creative workings has been possible because such consciously integrative dynamics are reordering how we think and perceive.

Our Multiple Intelligences

Below are more detailed descriptions of the our multiple intelligences as defined by Creative Systems Theory

The Intelligence of the Body:

God grant me from those thoughts men think

From the mind alone,

He that singa a lasting sone

Thinks in a marrow bone.

—William Butler Yates

The earliest knowing in any life process is bodily knowing. Developmental psychologist Jean Piaget speaks of the early intelligence of the child as “sensory motor” knowing. The infant’s reality is organized kinesthetically, as interplaying patterns of movement and sensation. Similarly, bodily understanding organizes reality in the earliest stages of culture. To a tribal person, truth lies in one’s bond with, and as, the creature world of nature. We live from this same place in the beginning moments of any process of creative manifestation. The first moments of new creative possibility are felt as “inklings,” kinesthetic sensings of life. In this first stage of creative reality, intelligence is “cellular.”

Body in this most germinal stage in creation is very different from the body as we conceive of it through the isolated and isolating eye of Modern Age understanding. It us much more than simply sensation; also much more than simply anatomy and physiology; and more than one side of an either/or: body versus mind, body versus spirit. In this first stage of formativeness is not something we have, but who we are. It is our intelligence. It is how we organize our experience of both ourselves and our world.

While we don’t usually give it much status in formal thinking, the knowing of bodily reality has a central place in the concrete experience of our lives. For example, if you say you love someone and you are asked how you know, eventually you will begin to talk in the language of the body. You know you feel love because when you are with that person your “heart” opens, there is a warm expanding in the area of the chest. This experienced “heart” cannot be found by dissection, but it is undeniably not only very real, but close to what is most essential in us.

While we are often unconscious of this organically kinesthetic aspect of experience, it never escapes us totally. We give it colorful expression in our “figures” of speech. We speak of feeling “moved” or “touched,” of being “beside ourselves” or feeling that something is “over our heads.” If we take the time, a lot of this sort of experience is available consciously. As a simple example, if I attune to it, I am aware that I feel my bodily connection to different people at different times in quite different ways. With one person I may be most aware of a sense of fullness and solidity in my belly or shoulders. With another, the vitality may be most prominent as a sense of animation in my eyes and face, or erotic arousal in my genitals. With some people our meeting touches very close to the core of my body; with others the bodily experience of meeting may feel much more peripheral, more “superficial.”

The Intelligence of Imagination, Symbol, and Myth:

Dreams are the true interpreter of our inclinations.

—Montaigne

Symbol—the vehicle of myth, dream, metaphor, and much in artistic expression—also speaks from close to the beginnings of things, though not quite so close. When a storyteller utters the words “Once upon a time…” it is more than simple convention. The words are a bidding to remember an ancient fecundity and magic.

The symbolic is, as I think of it, both the organizing truth and the major mode of expression in the second major stage of formative process. As myth, it serves as truth’s most direct expression in the times of early high cultures: in ancient Egypt, early Greece, for the Incas and the Aztecs of Per-Columbian Meso-America. As imagination, it defines the reality of childhood: the essential work of the child is its play, the trying out of wings of possibility on the stage of make believe and let’s pretend. The symbolic is present in a similar way with the beginnings of any creative task. It organizes reality in the stage of inspiration, that critical time when bubblings from the dream work of the unconscious give us our first visible sense of what is asking to become.

Joseph Campbell described the mythic aspect of the imaginal this way in Myths to Live By: “It would not be too much to say that myth is the secret opening through which the inexhaustible energies of the cosmos pour into human cultural manifestation. Religion, philosophies, social forms of primitive and historic man, prime discoveries in science and technology, the very dreams that blister sleep boil up from the basic magic ring of myth.”

The Intelligence of Emotion:

The perception of beauty is a moral test.

—Henry David Thoreau

The next intelligence in this development sequence is more familiar to us than the first two. It is one step closer to the rational sensibilities that today we are most likely to identify with truth. This is the language of emotions.

While more familiar, beginning to think of the affective as intelligence stretches usual understanding in a couple of key ways. First it becomes an integral part of not just of understanding, but also of theory. In the past, we have specifically cleansed the emotions from our theoretical formulations so that our ideas would have the rigor needed for objective truth. Second, we necessarily engage the emotional in a deeper sense than we are accustomed to. The emotional as we have known it in our current stage in culture is only a faint vestige of the feeling dimension at its full grandeur as a primary organizing reality.

The emotional orders truth in the third major stage of formativeness. When it is preeminent, life is imbued with a visceral immediacy, and strong ethical and moral responses. We can feel its presence in the fervencies and allegiances of adolescence. It is there in a similar way in the crusading ardency and codes of honor and chivalry of the Middle Ages. And we see it in the courage to struggle, and the devoted commitment, necessary to take any personal experience of creative inspiration into manifest form.

In conventional thinking, we acknowledge just the most surface layers of this part of us. We treat the emotional as, at best, decoration, or as a pleasant diversion from the real stuff of understanding. That somehow we must reengage this aspect of ourselves as an integral part of how we know truth becomes obvious if we examine the issues that now confront us as a species. Solving the dilemma of our future will require a keen sensitivity to the fact of human relationship and deep levels of personal integrity and ethical responsibility. It is our emotional selves that most appreciated and understands these sorts of concerns.

The Intelligence of the Intellect:

Cogito ergo sum—I think therefore I am.

Rene Descartes

The rational (rational/material intelligence) is what we measure with IQ tests and most engage and reward in traditional education. It is the intelligence of syllogistic logic—if A, then B, then C. In creative work, it comes most strongly to the fore with formative process’s time of finishing and polishing. With individual psychological development, it orders adult understanding. And it represents the kind of cognitive processing that we equate almost exclusively with intelligence in modern times.

This is not to say that rational processing doesn’t have a place in the cognitive processes of earlier cultural times. But depending on the cultural stage, the underlying premises of our “logic” will have their roots in the pertinent (often decidedly non-rational) organizing sensibilities. In earliest times, for example, our “logic” will reflect underlying animistic (body intelligence) assumptions. Imagine two cave dwellers discussing the various creatures depicted on a cave wall.

With Late-Axis culture and its Age of Reason, the underlying premises of our logical assertions came to have their roots as well in rational/material assumptions. Rationality became allied with awareness and perceived as itself truth—“objectivity” set in polar juxtaposition to the merely subjective (a catchall category for all the previously reigning intelligences). As it did so, truth and value came increasingly to be described in material terms—causality in the language of actions and their concomitant reactions, and wealth and progress in terms of material acquisition and invention.

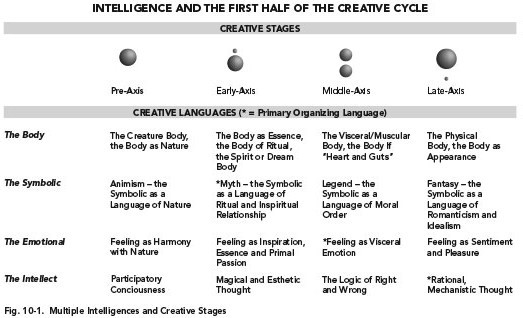

Beyond One Intelligence, One Stage:

In order to keep things simple, throughout most of this site, I will speak as if we can identify each intelligence with a particular creative stage. But if we wish to bring nuance and sophistication to our thinking, we need to appreciate how each intelligence has a role to play at each creative stage. It is true that particular intelligences most define understanding at particular creative stages. But in a similar way to what I just suggested for rational intelligence, with each stage within any particular scale of formative process each intelligence manifests in a particular way as part of the larger sensibility that orders that stage’s generative task.

As a further example, let’s take imaginal/symbolic intelligence as it takes expression at different stages in culture as a creative process. In tribal times, while imaginal/symbolic intelligence takes a back seat to bodily knowing, it nonetheless has an important role, manifesting as animistic imagery with its clear message of inseparability from nature (remember our cave dwellers). With Early-Axis culture, imaginal/symbolic intelligence steps forward to become intelligence’s most determining voice. It is here that we find pantheons of gods, great mythic tales, and, more so than at any other time, artistic expression treated as a direct expression of truth. With Middle-Axis culture, while imaginal/symbolic intelligence again takes a more secondary role—in this case to emotional/moral intelligence’s now defining presence—it continues to contribute. Myth’s numinosity gives way to the more explicitly moral sensibilities of legend—think of the medieval tales of the Knights of the Round Table. And while art ceases to be itself a definer of truth, it continues to serve powerfully as a language for religious sensibility. With the Late-Axis times, imaginal/symbolic intelligence comes to have clearly diminished significance as we now relegate it to the separate-world reality of the subjective. We may still appreciate it—indeed the arts can have an elevated presence. But increasingly its role is decorative, manifesting at its most superficial in Walt Disney–style fantasy.

The chart below from The Creative Imperative summarizes the ways each of the primary intelligences identified by Creative Systems Theory takes expression at different stages in formative process.

\