Adapted from Cultural Maturity: A Guidebook for the Future

Just what does it mean to be embodied? Bridge mind and body and it becomes a new sort of question—and certainly one of big-picture significance. CST not only invites a larger picture, it provides a way to map body realities and body dynamics. The way CST helps us begin to reconceptualize body dynamics may, in the end, be one of its most important contributions. It is has not been elaborated extensively in writing because the whole notion of thinking of the body in terms of intelligence is such a stretch for most people.

If I could know in advance the future’s answer to one health care question, my choice would be immediate: “What is a body?” On the surface, the question “what is a body” might seem simple to answer. We need only look down; there it is. In fact, the question is not at all simple. Certainly it is perplexing philosophically. The body is at once something we have and something we are—not an easy fact to reconcile. And the question increasingly confronts us in eminently practical ways—when we consider the body scientifically and medically. We are used to inquiring about how neurons work, about the biochemistry of digestion, or about the role of genes in disease. But increasingly we recognize we have only begun to to understand the body’s rich systemic complexity.

Part of the reason we have more to learn is simply that there is research yet to be done. But the reason, at least that we could miss all that we do, has much to so with how we think. I’ve observed our Modern Age tendency to view a machine model of understanding as sufficient and culminating. And Transitional culture, with its near absence of lower-pole sensibility, would be expected to distance us even further from anything more than the most rudimentary action-reaction notions of bodily functioning. I’ve described how disconnected we can be from bodily experience as a particularly consequential Transitional Absurdity.

The importance of understanding living systems in ways that better reflect the fact that they are alive applies in a way that has particular significance to the question of what it means to support good bodily functioning. If health and healing are about anything, they are about enhancing life. We’ve always known at some level that healing was more complex than fixing broken anatomy. I am reminded of Benjamin Franklin’s quip, “God heals and the doctor takes the fees.” But before now, the implications have most often been more than we could handle.

The notion that we can speak of the body a “intelligence” has similarly become newly important. And similarly it stretches us in fundamental ways. I’ve commented on the trickiness of talking about the body as a way of knowing, given how in our times we have so little connection with the body as experience. But I’ve also emphasized the essential role that body intelligence comes to play with culturally mature understanding. In particular I’ve emphasized its pivotal significance in a creative picture of cognitive functioning.

When we “bridge” mind and body—as culturally mature perspective always does—the question of just what it means to have a body becomes a new sort of question. It also, in a whole new way, becomes a question of deep significance. The what-is-a-body question presents anther eternal quandary for which developmental/evolutionary perspective offers new insight. Creative Systems Theory not only invites us to consider a larger picture, it provides us with a way to map body realities and body dynamics.

Here, very briefly, I will draw on Creative Systems Theory’s framing of bodily experience in a couple of ways. First, I will address the different ways we experience bodily intelligence at different stages in any formative process. I will then turn to how, with each stage in formative process—including culture as a formative process—we not only experience what it means to have a body in particular ways, we inhabit our bodies in particular ways.

I’ve spoken of each creative stage being ordered by a different intelligence. Earlier in this chapter I added a further level of detail by outlining how each intelligence—bodily intelligence included—manifests in each stage, but in different ways. The following descriptions, drawn from The Creative Imperative, fill out this progression. It also links the progression to how health and healing have been perceived at different times in culture’s story:

Creative Systems Theory calls the body of earliest times the “creature body.” This is the body that knows the tribal dances and that moves in harmony with the beings of the forest, the skies, and the oceans. Disease in tribal cultures is most often thought to follow from breaking taboos. Beneath the surface of taboos we find actions that violate and put at risk the fundamental inseparableness from tribe and nature. Treatment is primarily through ritual and the application of healing herbs, its purpose to restore that inseparableness.

Creative Systems Theory calls the next body the “energetic body.” Here the body becomes less creaturely and more a vessel of energies and essences. We find this layer of bodily perception and conception today in the acupuncture meridians of traditional Chinese medicine and the chakras of India’s yogic traditions. Disease in early classical times, in both East and West, is thought to result from imbalances between energetic tendencies. Healing can be through manipulation, meditation, or herbal remedies, its purpose being to reestablish inner balance.

Creative Systems Theory calls the third body in this developmental sequence the ‘visceral/muscular body.” From late classical Greece until well into the Modern Age, the body in the West was conceived of in terms of emotion-laden fluids—blood, phlegm, yellow bile, black bile. (Here lie the roots of words like “bilious” and “phlegmatic.”) Disease, then, was thought to have its origins in sinful acts or conflicted relationships and to manifest as blockages in the movement of these fluids. Healing practices—the administration of medicines, crude surgery or manipulation, religious absolution—were designed to remove these blockages.

The final body in this sequence—or at least the one we know from most recent times—is our familiar body of anatomy and physiology, the Modern Age’s body as great machine. Modern medicine views disease as damage to that machine—the cause being variously trauma, microbes, genetic defect, or wear and tear. The purpose of healing, whether through surgery or the prescribing of drugs, has been to repair broken tissues and restore its functioning.

Which is the real body? Were early conceptions simply naïve? In major ways, certainly they were—especially when it comes to implications for health and healing. The greater portion of the knowledge we draw on today, including discoveries as basic as the role of bacteria and viruses in disease, is remarkably recent. But Creative Systems Theory suggests that differences in how we’ve understood the body may also reflect our complexity as much as our past ignorance. If the concept of Reengagement holds, we would expect each of our earlier ways of understanding the body to have at least something to teach. Indeed, given that modern cultural realities have inherently the weakest connection with bodily experience, we might expect earlier ways of thinking about the body to provide some particularly useful insights.

When it comes to health care, earlier views of the body at the least point toward the importance of including more than just physical factors in our considerations. The perspective of the “visceral/muscular body” adds that we must also consider a person’s general emotional/moral well-being and the health of relationships. The perspective of the “energetic body” adds that we must include too a person’s sense of balance and life direction. And the perspective of the “creature body,” adds that we also need to take into account the health of one’s felt connection with nature, spirit, or group—with things larger than oneself. A person might object that these factors have more to do with psychology than medicine—and at least from an isolatedly “physical body” perspective, that would be accurate. But when we begin to bridge mind and body, these observations begin to have larger consequences. If the future of medicine is about anything, it is about learning to address the body as somebody.

Medicine can also learn from how these various “bodies” suggest a more animated, indeed intelligent, picture of bodily functioning. Increasingly, today, we recognize that other aspects of the body than just the nervous system are “intelligent”—in the sense that they learn and also direct complex evolving processes. I think in particular of the immune system (that among other things constantly creates new anti-bodies to fight disease), the digestive system (that manages an intricate ecosystem of supportive microorganisms) and the endocrine system (that organizes complex hormonal responses). We are just beginning to grasp what this more dynamic—indeed “creative”—picture of bodily response may mean for the future of medicine. But we can be sure that engaging the body as somebody must also better include the whole of how we, as bodies, choose, learn and communicate.

And specific interventions from earlier times can be at least provocative—perhaps invite is to entertain options we might not have thought of. For example, I find it fascinating that while Western medicine has begun to make limited use of acupuncture, it has yet to explain acupuncture’s effectiveness in any satisfying way. We can’t help but wonder what even greater mysteries we have yet to explain—or even recognize.

It is important to appreciate that we’ve never really just studied the body—objectively stood back from it—even the modern scientific body. We’ve always studied mind/bodies, albeit of different sorts (and being mind/bodies ourselves, never from a purely objective perspective). Creative Systems Theory proposes that how we experience our bodies today reflects a particular time-relative and space-relative relationship between mind and body. It also proposes that this felt relationship is changing. I suspect that in the twenty-first century, the body will provide many of humanity’s most dramatic and important new leanings.

The second way of approaching who we are as bodies turns to an important way that we can use how bodily experience organizes creatively to help us more deeply understand Creative Systems patterning concepts. I’ve emphasized that every Creative Systems concept requires each of our multiple intelligences if we are to fully understand its implications. Bodily intelligence contributes to understanding in some particularly graphic ways. We can think of Creative Systems patterning concepts not just as useful abstractions, but as ways of describing different ways of being in our bodies. Creative Systems Theory maps this dynamically systemic picture. It describes how what it means to be embodied evolves in a characteristic manner over the course of any formative process, and also similarly manifests in characteristic ways with here-and-now creative differences.

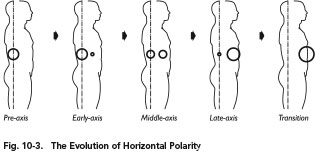

I’ve observed how polarity has both more horizontal and vertical aspects. The words are more than just metaphorical. They reflect different ways experience is embodied. The diagram below—from The Creative Imperative—depicts how horizontal polarity manifests differently depending on when and where we find it. It can be applied equally well to Patterning in Time and Patterning in Space observations.

The diagram in Figure 10-4 adds vertical polarity to the representation and depicts how horizontal and vertical polarity together generate our felt experience of ourselves and how we perceive our worlds. Also from The Creative Imperative, it similarly can be applied to both Patterning in Time and Patterning in Space observations.

How does our actual experience of being embodied change with Integrative Meta-perspective? We become more in touch with bodily experience, certainly, better able to read our body’s cues and derive fulfillment from the life of the body. There are also deeper rewards. A client described the changes this way. He observed that early in his life he had felt rooted in his beliefs. Then those beliefs were challenged and he went through a period where he felt that he had no roots. As he developed more culturally mature sensibilities, increasingly he felt “rooted in the fact of rootedness.” The way Reengagement gives us a new, more complete relationship to bodily